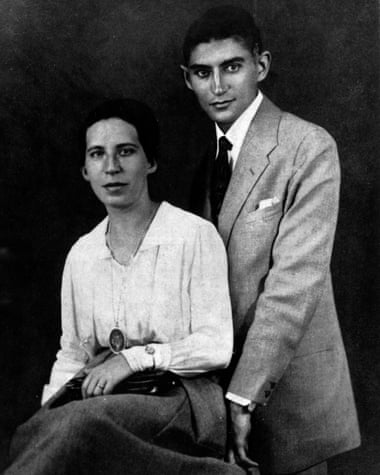

Kafka and Women

Franz Kafka was a man of contradictions.

While he needed women and sex in his life, he had low self-confidence, felt sex was dirty and was shy—especially about his body.

Kafka had cultivated an internal conflict between contradictory and mutually exclusive forces. The yearning for company versus the need for solitude, his desire to be married versus his distaste for cohabitation and physical contact, the wish to start a family versus the requirement of a monastic lifestyle, the need for employment versus the vital need to write – all of these constituted a vicious cycle from which there was no escape.

His relationships were not spared in this conflict.

Three women who greatly impacted his life were Felice Bauer- his longest love, Milena Jesenka - an intelligent woman with whom he had a complicated relationship and Grete Bloch - An intermediary and minor flame between his relationship with Felice.

Felice Bauer

She was Franz Kafka’s longest and most complicated love, his first fiancée. She was from Upper Silesia, her mother’s birthplace. Her father worked as an insurance agent. She had three sisters and a brother. In 1899, the family moved to Berlin. Felice attended a Handelsschule (a vocational school for commerce) but had to give it up because her family could not afford it. Felice worked for a short period in the offices of the Odeon, before transferring in 1909 to the Carl Lidström Company. Felice met Kafka in Prague on 13 August 1912. Kafka wrote about her in his diary, describing her, his words flowery and infatuated. During World War I, Felice was attracted to Zionism. Felice worked with as a teacher and Kafka lent her moral support.

Soon after the meeting, he began to send her almost daily letters, expressing disappointment if she did not respond as frequently. He dedicated his short story "The Judgment" to her. Between 1912 and 1917, Kafka sent her almost 600 letters and postcards that mirror the ups and downs in their relationship. It was a ‘pen romance’, their personal encounters having been relatively few in number.

Felice was an extremely capable, practical and orderly woman. She had middle-class tastes and no great feeling for art or literature. Kafka admired her temperament, but it tended to complicate their relationship. She wasn't a match for Kafka in his complex struggle between marriage and solitude. She failed to understand the battle Kafka was waging with himself.

After a determined struggle, their relationship culminated in two engagements, one in 1914 and another in 1917 and was canceled immediately on both occasions.

Five years before her death, Felice placed the letters sent by Kafka to her and her friend Grete Bloch at the disposal of Schocken Publishers in New York. They were published in the 1960s.

Reflection as a Feminist voice

Felice shows that women were important to Kafka. He supported Felice's work as a teacher and admired her tastes and temperaments. Yet it was his own indecisiveness that made him push the love of his life away. He was a pretty bad boyfriend but did not force her to stay with him, as would have been acceptable at the time.

· Milena Jesenská

Both Czech and Christian, she was the second great love of Kafka’s life. She was the daughter of Jan Jesenský, a professor of dental surgery in Prague. Jesenský was a well-known member of Czech high society. Milena lost her mother at the age of thirteen. She attended the Minerva high school, the first private Czech high school for girls, from which the first emancipated women intellectuals emerged, championing a new, freethinking lifestyle in an era where it was unacceptable. Erratic family circumstances and the emancipatory views of the Czech-German Prague intellectuals brought this vivacious, energetic and flighty young woman into open conflict with society.

In 1917, she was having an affair with Ernst Pollak, a bank clerk, well-versed in music and literature, She married him at the age of 21 and left with for Vienna. Pollak was a member of Franz Werfel’s circle that Kafka would occasionally join. In Vienna, Pollak publicized the work of the then little-known Prague writer, Franz Kafka. It was he who brought Kafka to the attention of Milena. Her German was good enough for her to try her hand at translating shorter German texts into Czech. Kafka’s story The Stoker was not the first work by a German author she had tried translating. As she was to do, she made written contact with the author about the translation of The Stoker, and their correspondence developed into an ‘epistolary novel’.

Kafka had feelings for Milena. Throughout 1920 letters streamed back and forth between Merano, Kafka was and Vienna, where Milena was living in an unhappy marriage. They met in person only twice. Their first meeting, in Vienna, was happy but their second, in the town of Gmünd, marked a hiatus in their relationship. They were poorly matched temperamentally, and Milena was unwilling to abandon Ernst Pollak, whom she loved in spite of their difficulties. Kafka’s relationship with Milena ended like the two previous ones. Out of it came Kafka’s Letters to Milena, an outstanding feat of letter writing, and Milena’s translations of Kafka, the first ever into a foreign language.

Reflection as a Feminist voice

Unlike many other men of his time, Kafka was not threatened by educated women. Milena subverted society by being a woman who graduated high school and thought freely. Despite meeting only twice, Milena had a huge effect on Kafka, as their correspondence carried on for years. Both the women Kafka considered his greatest loves were educated to a degree; Felice had to drop out because of monetary issues while Milena completed her education. It is telling of Kafka that he did not scoff at a woman wanting to translate his text but rather wrote back with encouragement.

Grete Bloch

She was a friend of Felice Bauer’s and five years younger. She was born in Berlin and held similar jobs to Felice. She was a mediator between Kafka and Felice during their first crisis. She worked for an office-equipment company and like Felice saw rapid promotion. She met Felice five months after Kafka, in early 1913. When, towards the end of that year, Kafka’s relationship with Felice foundered for a while, she went off to Prague as an intermediary. She and Kafka then corresponded regularly for a year, with Kafka writing her over 70 letters.

Grete Bloch subsequently played a major role at the ‘tribunal’ in July 1914, when the engagement between Felice and Kafka was broken off. Grete presented Kafka’s letters which were humiliating to Felice. She maintained her friendly ties with Felice. In the 1930s, she willingly left Germany into exile, going first to Israel and later to Italy. At that time she handed some of the letters she had received from Kafka over to Felice Bauer.

Reflection as a Feminist voice

Kafka was a terrible boyfriend. Men usually mediated arguments but in the case of Felice and Kafka, Grete did. She was a woman with strong beliefs and was ready to step to the occasion as it presented itself. She was unafraid and presented Kafka's letters to the tribunal, despite the potential backlash. Grete seems to have inspired Kafka, as he chose her name for the female lead in 'The Metamorphosis'.

Comments

Post a Comment